Hello

News

- Home

- News

Quick Links

Social Conversation / Health Forum

- AI regulation in healthcare

- Relaxation in restrictions to supply food aid to end malnutrition and hunger deaths in children

- Can do mindset of healthcare professional can facilitate transformation of virtual healthcare delivery to aged care residents in Australia

- Private health insurance premiums to rise by 3.73% from April

- WHO funding in changing world

Ask Your Health & Fitness Question

"Timely and confidential expert opinion on health matters"

Timely healthcare advice available to you from healthcare experts using Telehealth services and Virtual care services

News

Back

A Fair Go in the age of Algorithmic ageism. Australias Fair Dinkum approach to to True Health Trends in the Age of AI

11/01/2026

The global healthcare landscape in 2026 is defined by an unprecedented accumulation of data. From Japan’s Diagnosis Procedure Combination (DPC) to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) repositories, nations have built massive digital vaults. However, a critical question remains as to whether these databases represent the true and genuine clinical trends of our populations, or are they merely reflections of administrative priorities?

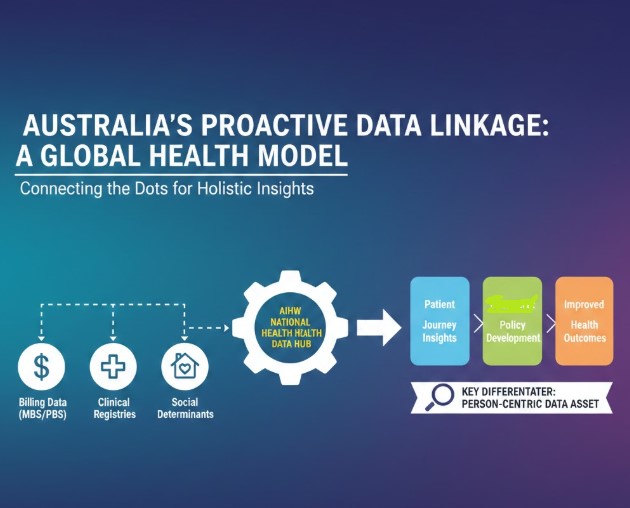

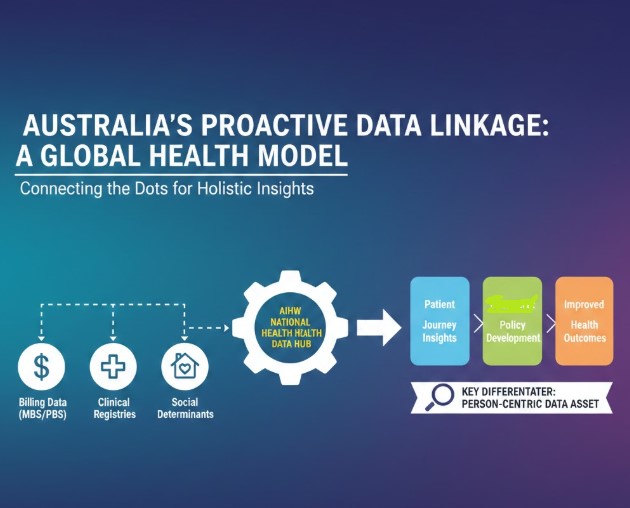

Australia is increasingly taking a proactive lead in ensuring that health data provides a true representation of the patient journey, moving beyond the "algorithmic ageism" that often haunts purely billing-focused systems.

The global data landscape portrays a pathcwork of intent. To achieve a representative view of health trends, we must first acknowledge that most national databases were not built for clinical discovery; they were built for payment. In Japan, the DPC covers 93% of acute beds but lacks the physiological "real-time" depth needed for AI. In China, the rapid expansion of the CHS-DRG system provides massive scale, yet often struggles to represent the true clinical trends of its 500 million rural citizens compared to urban hubs like Shanghai.

The most significant hurdle to "true representation" is the Evidence Paradox. In Japan, Australia, and China, the ageing population in the last fifteen years of their life time utilize the most resources but are the least represented in the clinical trials that set the standards of care or contribute to policy making.

When AI models are trained on administrative data alone, they risk codifying Algorithmic Ageism. An AI might see a trend where 85-year-olds receive fewer invasive interventions and "learn" that these treatments are futile. It misses the "fair dinkum" reality, that the absence of a procedure might be due to a compassionate Advance Care Planning (ACP) discussion or a cultural preference for comfort nuances that billing codes simply cannot capture.

Australia is distinguishing itself by proactively ensuring that "efficiency" does not come at the cost of "equity." The Australian strategy focuses on three pillars of true representation.

The first pillar includes the clinical data linkage. Australia doesn't just look at the bill but it links AIHW data with specialized registries (like the ICU-focused JIPAD-equivalents). This adds the necessary physiological layers like frailty scores and lab results to ensure AI interprets an elderly patient’s status accurately

The second pillar includes the the Indigenous data sovereignty: Australia leads in ensuring that health trends for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are interpreted with cultural safety. This prevents AI from misinterpreting socio-economic barriers as medical non-compliance, ensuring a "fair go" for minority populations.

The third and the most important pillar includes the role of clinicians as data stewards. Australia is fostering a generation of digitally literate medical professionals. These clinicians are the "translators" who ensure that policy-level AI doesn't just crunch numbers, but understands the human context of the hospital ward.

Australian approach provides an opportunity for ethical reflection on this critical matter. True representation is a moral imperative. In diverse nations, if an AI is trained primarily on the "average" urban patient, it fails to represent the unique health trends of rural or migrant populations.

To bridge this gap, future policies must be shaped by those who understand both the bedside and the database. Data stewardship is not just about privacy; it is about the integrity of the narrative. Qualified medical professionals must contribute to policy to validate audit for bias, trends ad incorporate crucial data such as fraility and daily living scales ( ADL) within national repositories.

In conclusion the global shift toward AI-driven health policy is inevitable. However, as Australia’s proactive model shows, the best way to ensure a "fair dinkum" future is to prioritize true representation over mere data volume. By empowering digitally literate clinicians to lead the way, we ensure that the national repositories Australia serve as maps of human health, not just ledgers of cost.

Back

Australia is increasingly taking a proactive lead in ensuring that health data provides a true representation of the patient journey, moving beyond the "algorithmic ageism" that often haunts purely billing-focused systems.

The global data landscape portrays a pathcwork of intent. To achieve a representative view of health trends, we must first acknowledge that most national databases were not built for clinical discovery; they were built for payment. In Japan, the DPC covers 93% of acute beds but lacks the physiological "real-time" depth needed for AI. In China, the rapid expansion of the CHS-DRG system provides massive scale, yet often struggles to represent the true clinical trends of its 500 million rural citizens compared to urban hubs like Shanghai.

| Country | Primary Repository | The "Fair Dinkum" Gap |

| Australia | AIHW / National Health Data hIB | Proactive: Linking billing data to clinical registries to get the full story. |

| Japan | DPC Database | Heavy on "what was done," light on the "clinical why." |

| China | CHS-DRG | Massive scale, but urban-centric data can skew regional trends. |

| UK | NHS HES | Universal reach, but can suffer from administrative "coding lag." |

| Singapore | TRUST / NEHR | Gold standard for multi-ethnic integration in a compact setting. |

| USA | HCUP / CMS Claims | Highly fragmented; trends often reflect insurance status over clinical need. |

The most significant hurdle to "true representation" is the Evidence Paradox. In Japan, Australia, and China, the ageing population in the last fifteen years of their life time utilize the most resources but are the least represented in the clinical trials that set the standards of care or contribute to policy making.

When AI models are trained on administrative data alone, they risk codifying Algorithmic Ageism. An AI might see a trend where 85-year-olds receive fewer invasive interventions and "learn" that these treatments are futile. It misses the "fair dinkum" reality, that the absence of a procedure might be due to a compassionate Advance Care Planning (ACP) discussion or a cultural preference for comfort nuances that billing codes simply cannot capture.

Australia is distinguishing itself by proactively ensuring that "efficiency" does not come at the cost of "equity." The Australian strategy focuses on three pillars of true representation.

The first pillar includes the clinical data linkage. Australia doesn't just look at the bill but it links AIHW data with specialized registries (like the ICU-focused JIPAD-equivalents). This adds the necessary physiological layers like frailty scores and lab results to ensure AI interprets an elderly patient’s status accurately

The second pillar includes the the Indigenous data sovereignty: Australia leads in ensuring that health trends for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are interpreted with cultural safety. This prevents AI from misinterpreting socio-economic barriers as medical non-compliance, ensuring a "fair go" for minority populations.

The third and the most important pillar includes the role of clinicians as data stewards. Australia is fostering a generation of digitally literate medical professionals. These clinicians are the "translators" who ensure that policy-level AI doesn't just crunch numbers, but understands the human context of the hospital ward.

Australian approach provides an opportunity for ethical reflection on this critical matter. True representation is a moral imperative. In diverse nations, if an AI is trained primarily on the "average" urban patient, it fails to represent the unique health trends of rural or migrant populations.

To bridge this gap, future policies must be shaped by those who understand both the bedside and the database. Data stewardship is not just about privacy; it is about the integrity of the narrative. Qualified medical professionals must contribute to policy to validate audit for bias, trends ad incorporate crucial data such as fraility and daily living scales ( ADL) within national repositories.

In conclusion the global shift toward AI-driven health policy is inevitable. However, as Australia’s proactive model shows, the best way to ensure a "fair dinkum" future is to prioritize true representation over mere data volume. By empowering digitally literate clinicians to lead the way, we ensure that the national repositories Australia serve as maps of human health, not just ledgers of cost.